KINSHIP, DATA &

DECENDANT ENGAGEMENT

BY JENNIE K. WILLIAMS, PH.D.

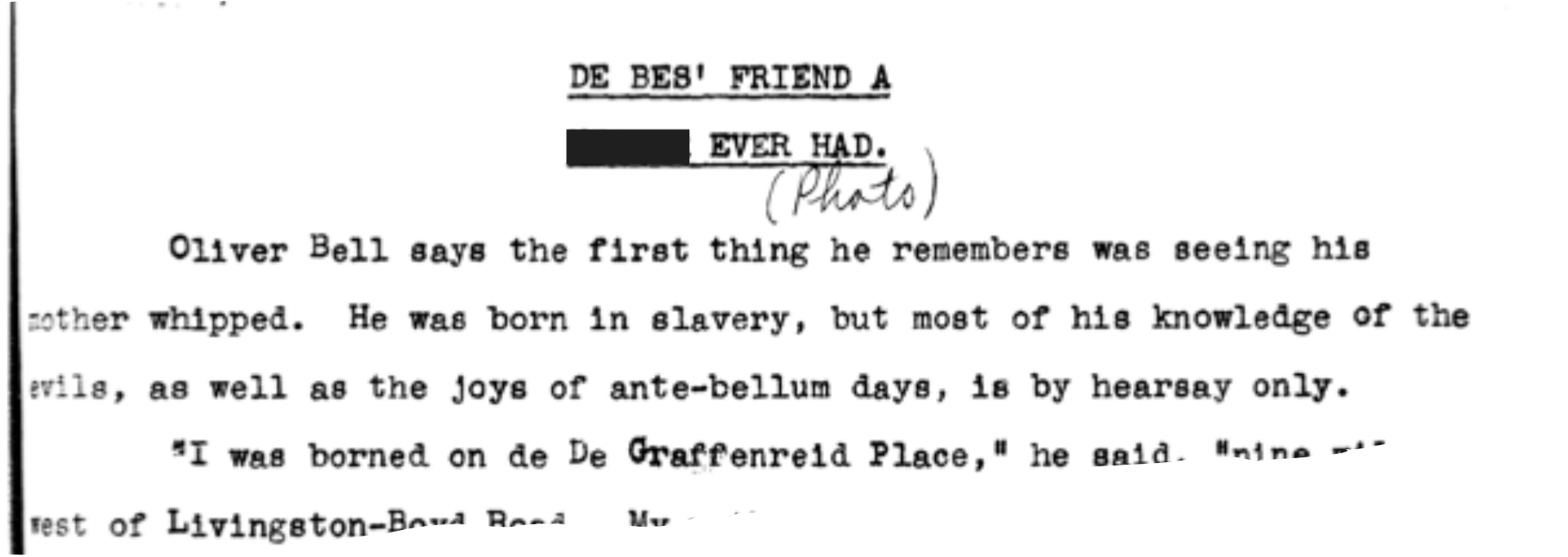

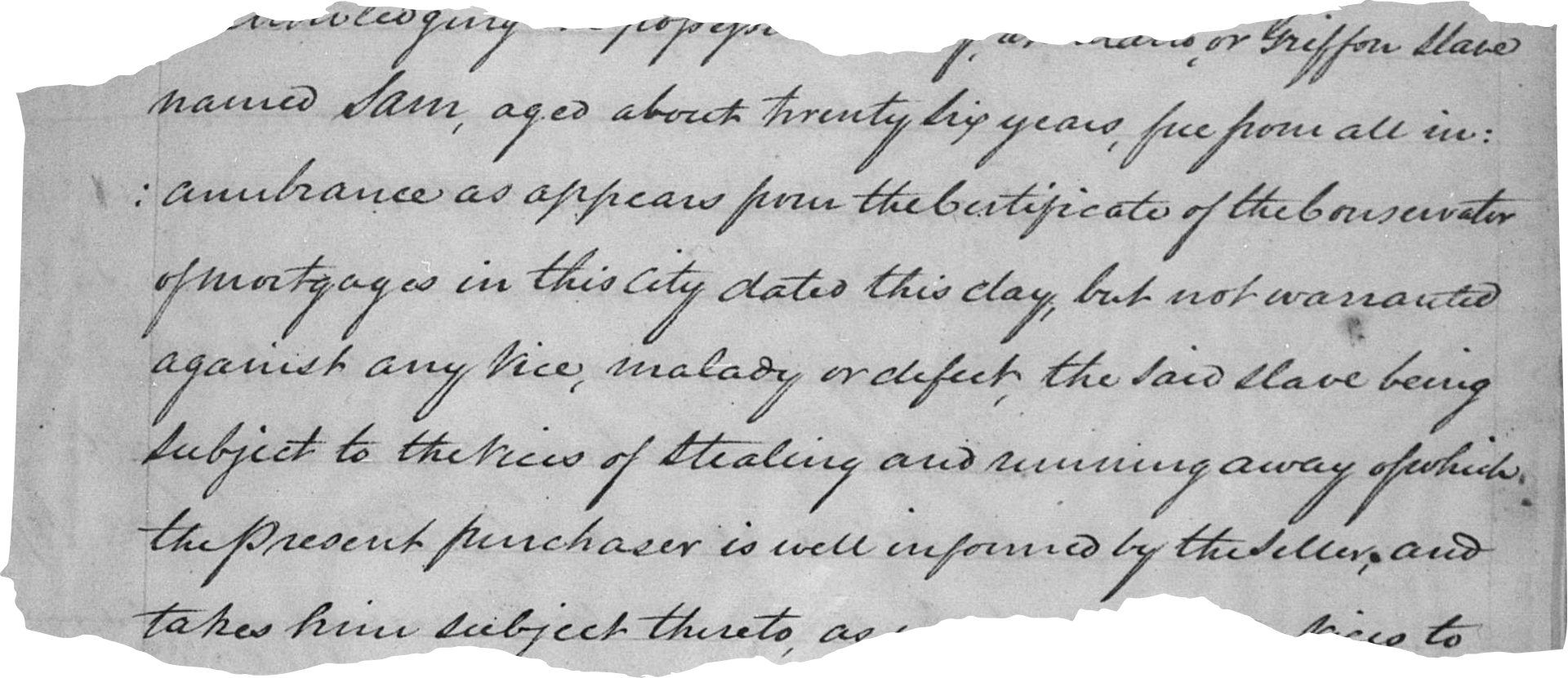

Considering the first line of James. W. C. Pennington’s 1849 narrative, the historian Walter Johnson has written that Pennington, a fugitive slave and abolitionist, intended to “trouble the boundary between ‘the slave trade’ and ‘the rest of slavery.’” Pennington’s point, Johnson tells us, was that regardless of where and by whom African Americans were enslaved, they were never safe from the worst slavery had to offer.

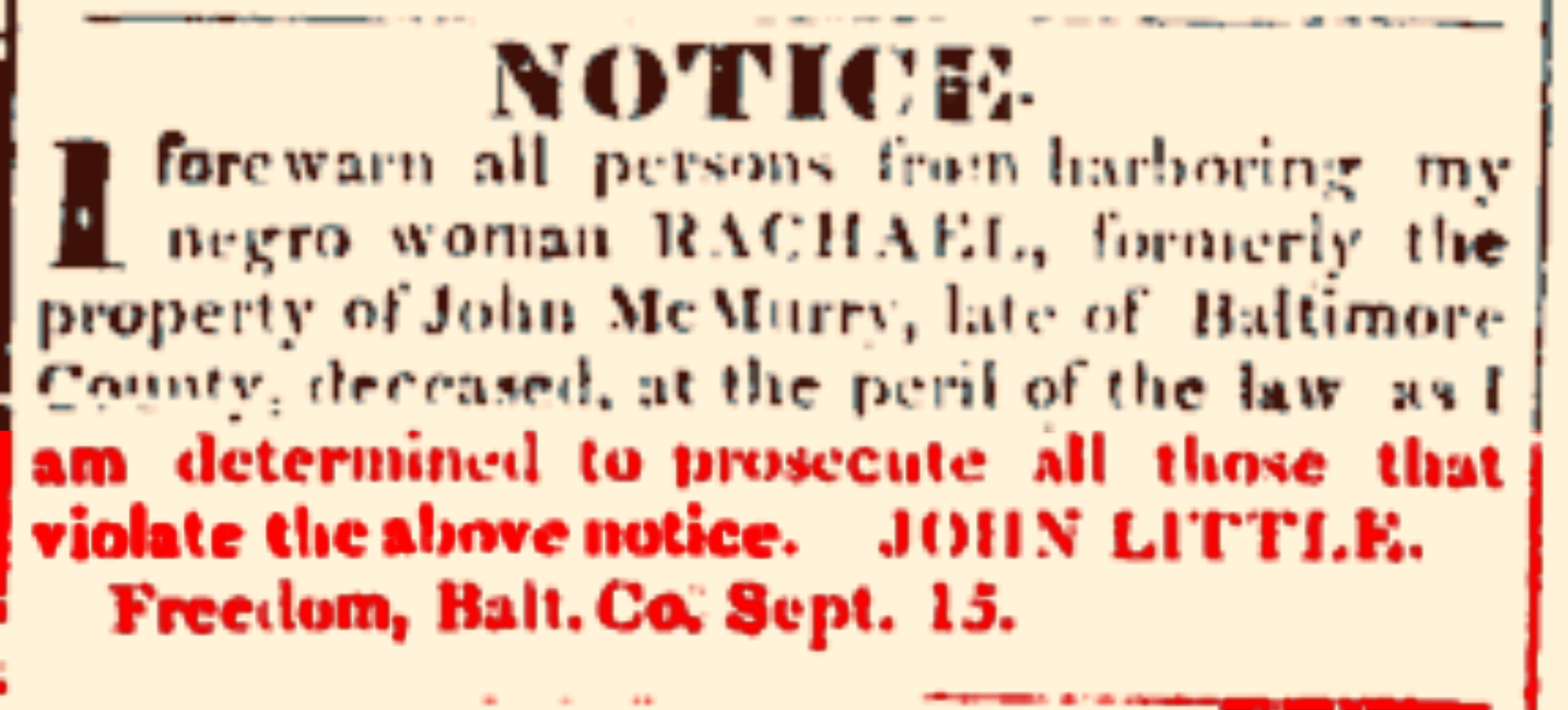

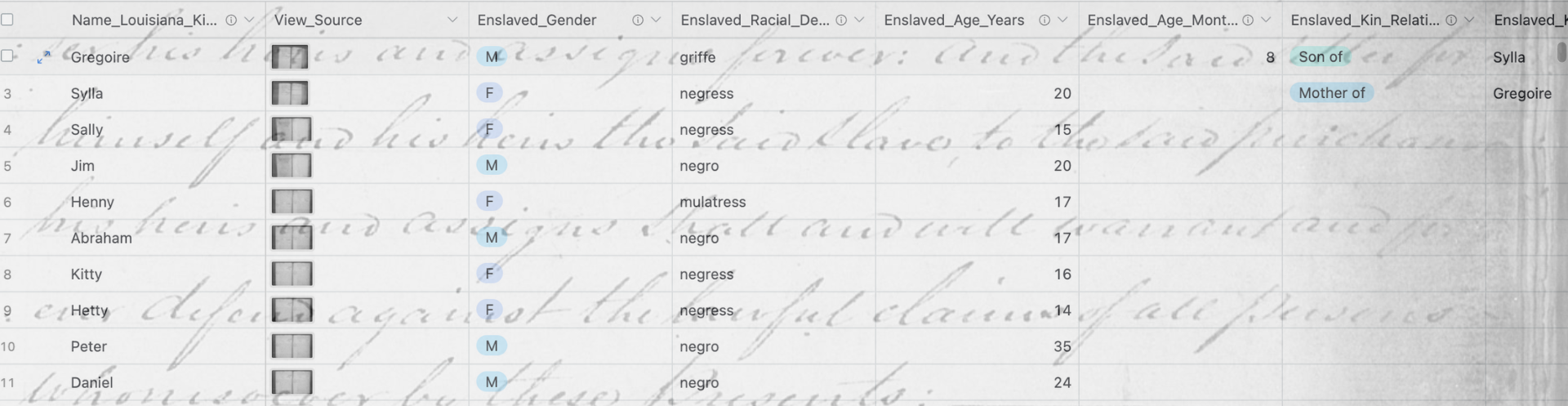

Johnson’s analysis is surely accurate. And yet, I wonder if we have overlooked the significance of Pennington’s addendum, “or relation.” It seems to me, that is, that Pennington’s point was not only about enslaved people’s perpetual vulnerability to slavery’s evils, but about the specific nature of those evils, which violated above all, enslaved people’s kinships and relational identities. According to the laws and logics of slavery, Pennington suggests, the enslaved maintained just one relation—that which exists between property and its price.