The Turner-Hines-Franklin Institute will lead the digital defragmentation of slavery’s global archive.

DIGITAL DEFRAGMENTATION OF SLAVERY’S ARCHIVE

NOUN/OBJECTIVE/CALLING

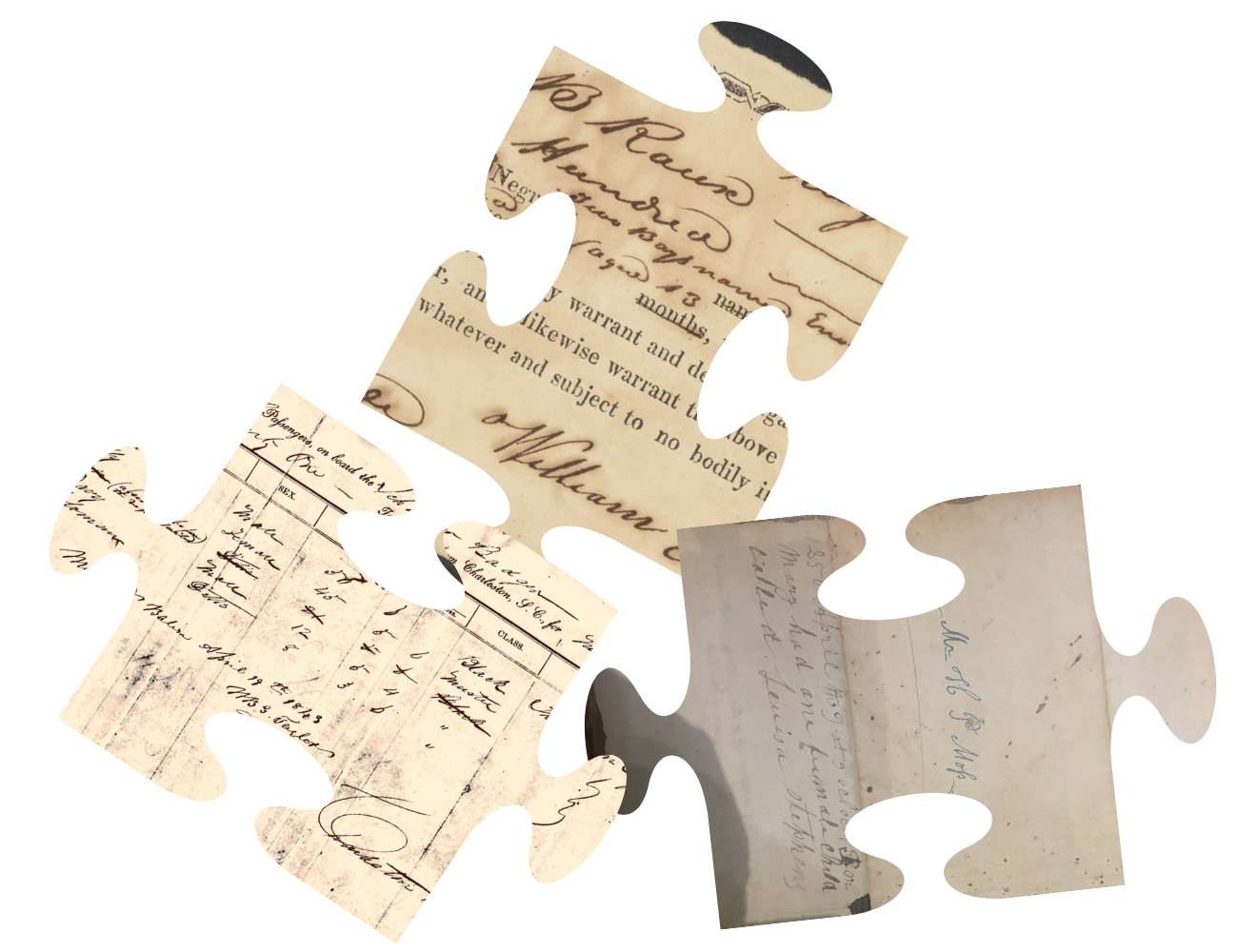

Using data and other digital tools to make disparate historical records from slavery publicly available and freely accessible and piecing these records together to reveal important truths about enslaved ancestors’ lives.

Why is digital defragmentation of slavery’s archive a necessity? And how does it work?

By law, enslaved people were prohibited from learning to read or write. For this reason, enslavers authored the vast majority of records relating to enslaved people’s lives, and most documents represent enslaved ancestors as property, not people.

Here’s another way of thinking about this…

Enslavers used documents as tools of exploitation, surveillance, and control. They were written and designed perform slavery’s foundational alchemy: the conversion of kin to commodity. And because this was their purpose, most provide just fleeting glimpses of enslaved ancestors: snapshots often taken in moments of grief or uncertainty, such as sale, forced migration, flight, or the division of families.

To be sure, it’s important to make records from slavery’s archive accessible—ideally in free and easily navigable databases.

However, digitization and dataification of records represent just the first two steps of the digital defragmentation of slavery’s archive, as seen in the example below.

Right now, historical databases are generally siloed from one another; there is no easy way of knowing, in other words, if an individual who appears in one database also appears in another.

Considering this problem as it relates to the Oceans of Kinfolk database, Jennie K. Williams has written:

“With only manifests in hand, individuals trafficked in the coastwise trade were—to us—memorically frozen in time, having neither past nor future. Suspended this way in the archive and spreadsheets, [Oceans of Kinfolk] denies enslaved people the right to be remembered as they were: human beings with befores and afters, and with kin and kindred who made that distinction meaningful.”

—Jennie K. Williams, “Finders Aren’t Keepers: Rethinking and Reconfiguring the Oceans of Kinfolk Database.” Journal of Slavery and Data Preservation 4, no. 3 (2023): 44-61.

For this reason, digital defragmentation of slavery’s archive also requires that we find a way to link disparate databases. This is a goal AI can help us achieve.

What will digital defragmentation of slavery’s archive achieve? Consider these examples…

The image below depicts one of the approximately 5,000 ship manifests Dr. Jennie K. Williams used to construct, Oceans of Kinfolk, the largest existing database of individuals sold in the domestic slave trade of the antebellum United States.

OCEANS OF KINFOLK includes the names of more than 63,000 enslaved men, women and children trafficked to New Orleans from domestic ports between 1818 and 1860.

Note that the Alfred’s captives included several children, the youngest of whom, Abram and William, were listed as seven and eight years old respectively. Listed sequentially on the ship’s manifest, William and Abram were probably standing next to one another as James McCulloch, Collector of the Port of Baltimore, drafted this document.

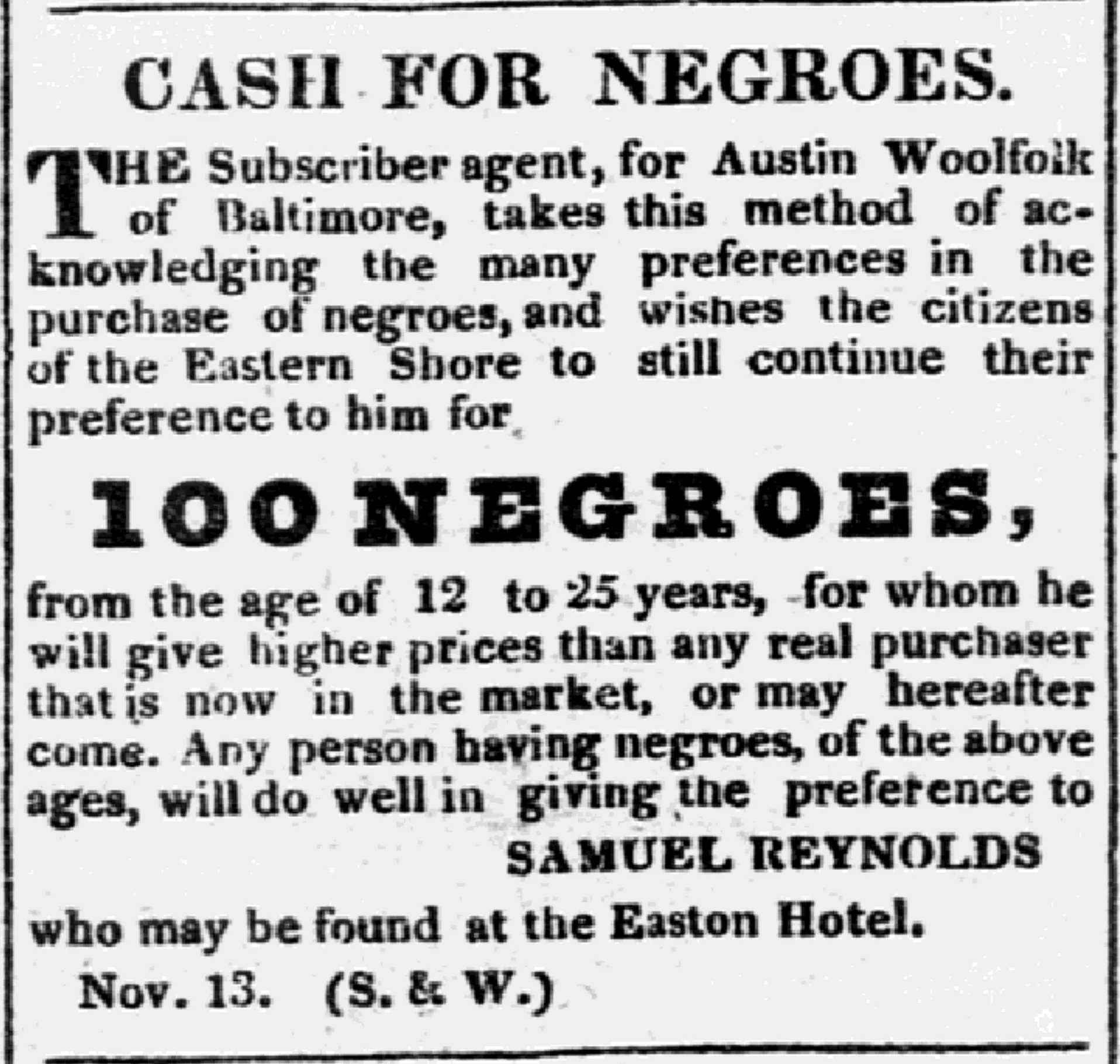

While younger than most, William and Abram were representative of the vast majority of the individuals identified in the Oceans of Kinfolk database in that they were trafficked to New Orleans by professional slave traders: men who made fortunes buying enslaved people in the upper south (especially Virginia and Maryland) and trafficking them to the lower south to be resold at a profit.

Baltimore Patriot, May 24, 1824.

Most descendants of individuals, like William and Abram, who appear in the Oceans of Kinfolk database have the same two questions.

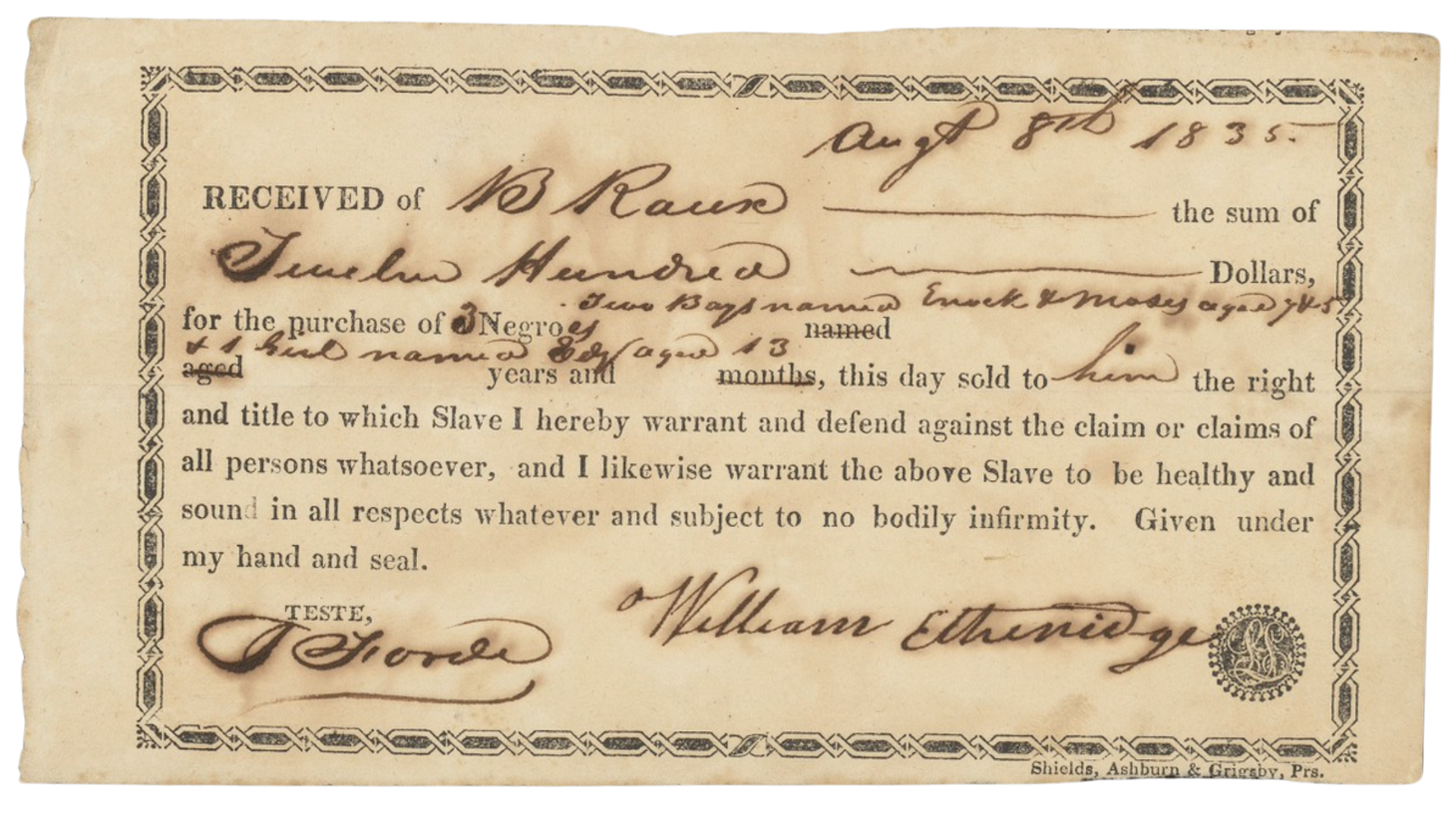

First, where were enslaved ancestors living before they were sold South to New Orleans? And second, what happened to them after their voyage to Louisiana? The THF Institute’s defragmentation of slavery’s archive will help us answer these and thousands of other questions. For example, through our partnership with the Maryland State Archives, the THF Institute is expanding the Legacy of Slavery Database to include information gathered from Maryland Land Records which document the sales of thousands of enslaved persons in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Easton_Gazette, February 12, 1831.

[TRANSCRIPTION]

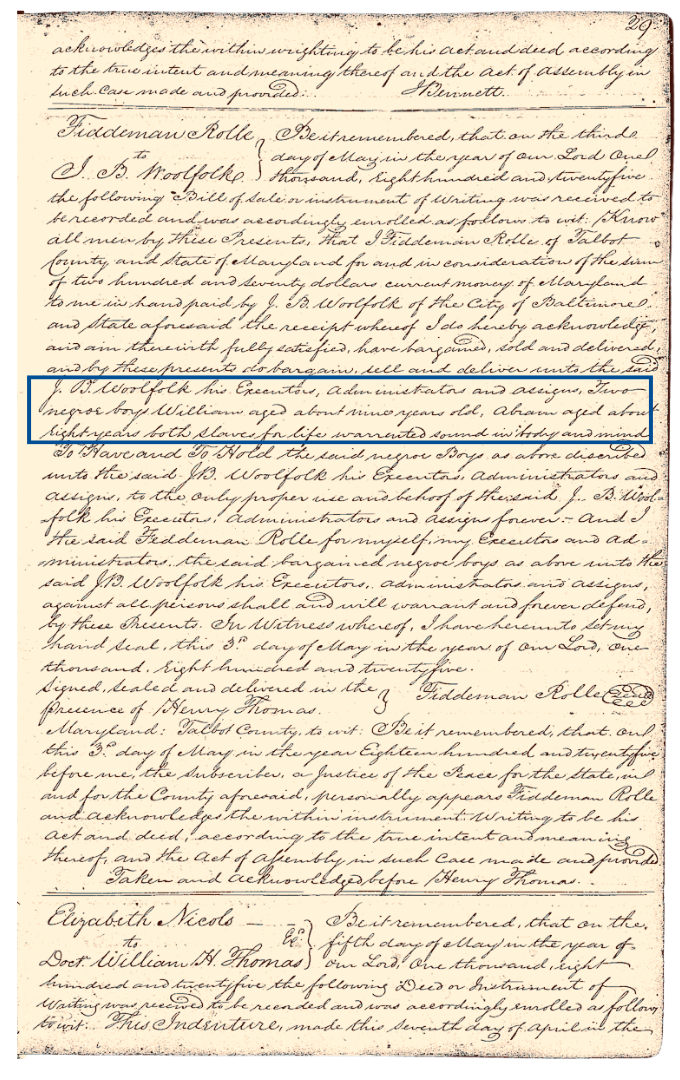

Fiddeman Rolle

to

JB Woolfolk

Be it remembered that on the third day of May in the year of our Lord one thousand, eight hundred and twenty-five the following Bill of Sale or instrument of writing was received to be recorded and was accordingly enrolled as follows to wit: “Know all men by these presents, that I Fiddeman Rolle of Talbot County and State of Maryland for and in consideration of the sum of two hundred and seventy dollars current money of Maryland to me in hand paid by J.B. Woolfolk of the City of Baltimore and State aforesaid the receipt whereof I do hereby acknowledge and am therewith fully satisfied, have bargained, sold, and delivered and by these presents do bargain, sell, and deliver unto the said J.B. Woolfolk his Executors, administrators and assigns, Two negroe boys William aged about nine years old, Abram about eight years both slaves for life warranted sound in body and mind.

To Have and to Hold the said negro Boys as above discribed unto the said J.B. Woolfolk his Executors, administrators, and assigns, to the only proper use and behalf of the said J.B. Woolfolk, his Executors, administrators and assigns forever. And I the said Fiddeman Rolle for myself, my Executor, and administrators the said bargained negroe boys as above unto the said J.B. Woolfolk his Executors, administrators, and assigns, against all persons shall and will warrant and forever defend by the presents. In witness whereof, I have hereunto set my hand seal, this 3rd day of May in the year of our Lord, one thousand, eight hundred and twenty-five.

signed, sealed and delivered in the presence of Henry Thomas

Fiddeman Rolle [seal]

Maryland: Talbot County to wit: Be it remembered that on this 3rd day of May in the year eighteen hundred and twenty-five before me, subscriber, a Justice of the Peace for the State in and for the County aforesaid, personally appears Fiddeman Rolle and acknowledges the within instrument writing to be his act and deed, according to the true intent and meaning thereof, and the act of assembly in such case made and provided.

taken and acknowledged before Henry Thomas.

Linking data from this record (from the land records for Talbot County, MD) to Oceans of Kinfolk reveals several important truths. From this record of the sale of William and Abram to the trader who sent them to New Orleans, we learn, at the very least, that the children knew each other prior to the voyage, and we can speculate that they were brothers.

By linking these records, in other words, we learn that William and Abram were and are from somewhere (Talbot County, MD) – that they were and are loved somewhere.

These are truths the children must have carried with them down the Atlantic and onto the auction block of New Orleans. And now—more likely than not—these same truths will compell William and Abram’s descendants to seek out and remember their stories, so long as we use data to lay out the archival trail correctly, and with care.

But defragmentation of slavery’s archive, however, requires that we go both forwards and backwards across space, place, and time. That’s why we’re also partnering with Freedom on the Move.

Launched in 2019, Freedom on the Move is the largest online repository of digitized newspaper advertisements for fugitives from slavery. At current count, the site contains information about more than 30,000 freedom-seekers. Linking Freedom on the Move to other datasets—including Oceans of Kinfolk—will radically transform the stories we are able to piece together and share about enslaved ancestors.

Here’s an example…

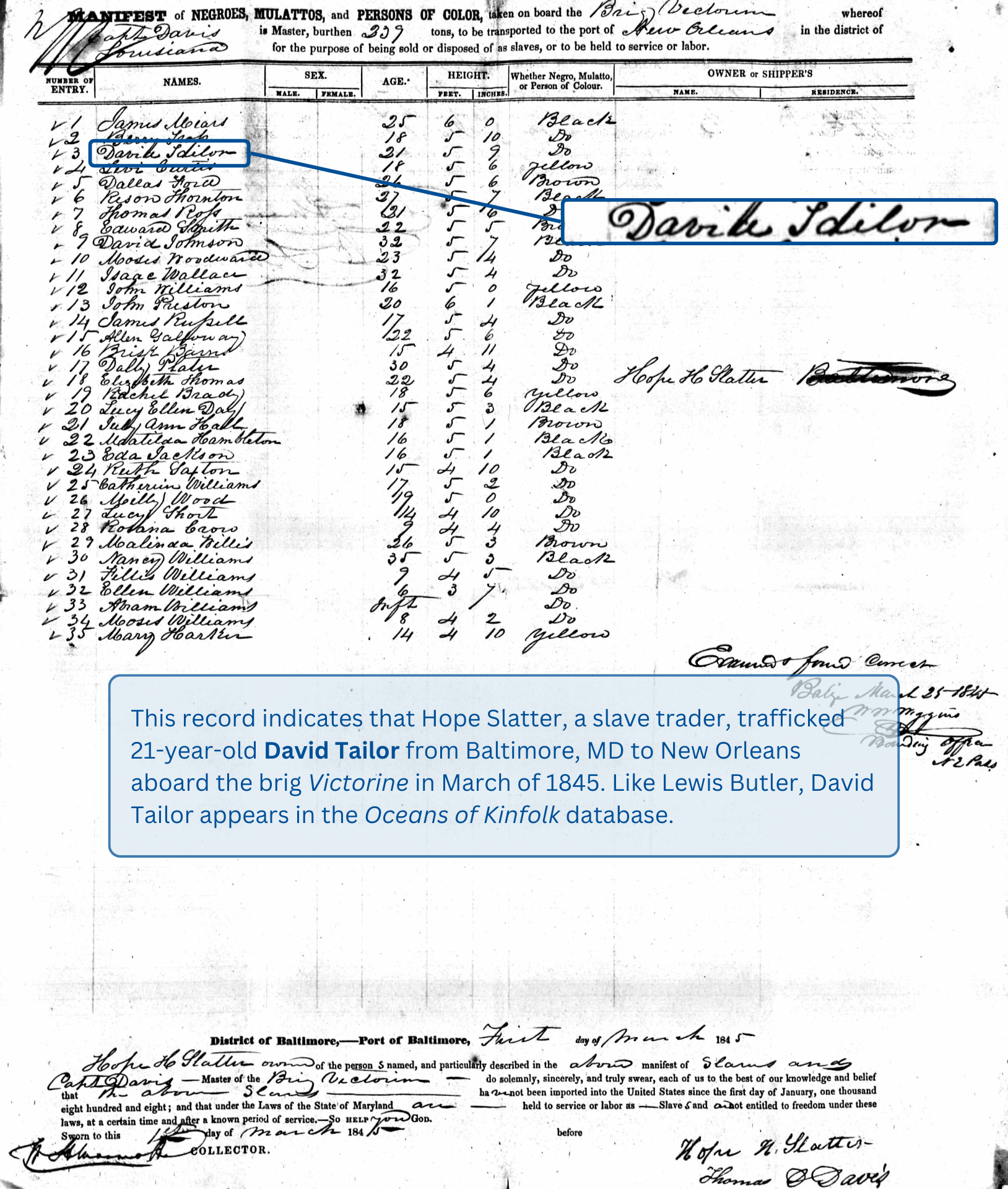

Pictured below are two of the records used to build the Oceans of Kinfolk database…

And here is one of the thousands of newspaper advertisement used to build Freedom on the Move.

Notice everything we learn by linking the data from these three records. First, we learn what happened to both men after their arrivals in New Orleans. Lewis was sold to D. Gandet, and David was sold to Valry Gandet.